| Edification value | |

|---|---|

| Entertainment value | |

| Should you go? | |

| Time spent | 77 minutes |

| Best thing I saw or learned |

The mansion has recently undergone a major wall upgrade, installing recreations of historic wallpaper based on Mme. Jumel’s descriptions. The Octagonal Drawing Room features an amazing pattern of clouds against a blue sky. I must remember that for the next time I renovate MY octagonal drawing room. |

The way to the Morris-Jumel Mansion takes you up the gentle slope of Sylvan Terrace, a single block long and one of the most unlikely streets in all of Manhattan. Paved with perfect cobblestones, both sides of the street consist of a matched set of beautiful, seemingly mint condition, wooden townhouses from the 19th century, all period charm and lovingly preserved detail. It’s a miracle that it survived, though the big white house on the hill at the end of the terrace is more miraculous still: the Morris-Jumel Mansion has lasted longer than any other home on the island, dating to 1765. That makes it about 30 years older than the Dyckman farmhouse, just a bit to the north. And instead of the Dyckman’s rustic, humble charm, Colonel Roger Morris built to his “summer villa” to impress.

Three stories (four if you include the basement), the grand house featured a columned portico and the first octagonal room in the country. Col. Morris and his wife, loyal to the British, abandoned the place during the revolution, leading to its moment in the spotlight of history. More on that later. In 1810, Stephen Jumel, an immigrant from France, bought the mansion. His wife, the smart and colorful Eliza Jumel (nee Bowen), has the strongest personality in the house today.

Madame Jumel

Eliza Bowen came from a poor family in Rhode Island. Not only did she find in M. Jumel a successful businessman to marry, but she turned out to be something of a real estate tycoon herself. The Jumels may not have been welcome in high society (being nouveau riche and from the wrong backgrounds), but they lived well. They spent time in France, and Madame Jumel (always “Madame,” it seems, never “Missus”) returned with (so she claimed) Napoleon’s bedroom set, and strong ideas about decorating her summer villa. No one’s quite sure if it really is Napoleon’s bedroom set, but just the fact that she’d tell people that brings her to life. She lived in the house until she died in 1865, apparently becoming quite eccentric over time.

Hamilton and History

As with all buildings of that vintage, my first question related to my favorite Founding Father. A.Ham indeed spent time there at least twice. Once during the period from September to October 1776 when Washington made the mansion his headquarters, before the British drove him and the Continental Army out of Manhattan. And again in 1790 when Washington held a cabinet dinner meeting there.

Also, the notorious A.Burr actually lived here–Madame Jumel married him in 1832, just a year after M. Jumel’s death. Briefly. It seems she got along with him no better than Hamilton did, though at least he didn’t shoot her. Rather, she divorced him. Practically unthinkable in that time, it confirms that he really must’ve been a colossal jerk.

ALSO also, Lin-Manuel Miranda asked if he could spend some time in the mansion while he wrote “Hamilton,” the better to immerse himself in the period vibe. So some portion of the musical came into the world in Aaron Burr’s bedroom at the Morris-Jumel Mansion.

That’s about as Hamiltonian as it gets.

The House Today

In addition to Napoleon’s alleged bedstead, the house has some original furniture, with about six rooms fully decorated, and another couple currently undergoing restoration. The kitchen space in the basement is open, but without much to see. As a fan of old kitchens, I hope they do something with it eventually. It does contain an odd display of a toaster, a chamberpot, a bedwarmer, and a teacup. Trying to figure out what those things have in common started to give me a headache.

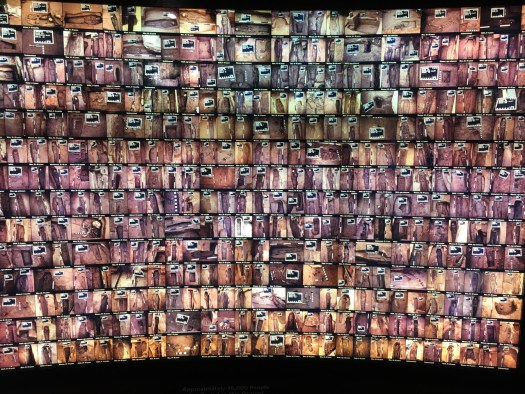

Each room has a rather handsome piece of modern wood furniture–a stand or a railing–designed to cradle an iPad. But no tablets in sight. I asked about that–whether it was an attempt at deploying technology that had failed. Turns out it’s still a work in progress. The tablets, when installed, will provide deep dives on individual pieces of furniture, paintings, and other objects. My skepticism of technology for technology’s sake in this sort of setting remains strong, but I like the idea of using screens to tailor descriptions to the needs and interests of visitors, enabling them to engage more deeply.

Trish, who was working the admission desk/gift shop that day, kindly answered my myriad questions, about technology and about history as well. She told me that it opened to the public in 1906, like the Van Cortlandt House a project of the Colonial Dames of New York. I asked how it survived, and she said Washington gets the credit: although only for a month, the fact that the mansion served as his headquarters earned its preservation. Indeed, when it first opened, the place served as a sort of shrine to Washington and the Revolution.

Only more recently has the story pivoted to focus on Madame Jumel, who after all lived there a lot longer, and about whose occupancy there’s a lot more historical information and documentation. And Napoleon’s bedroom set.

The mansion’s vast land holdings at one point stretched the (albeit pretty narrow that far north) width of Manhattan. All that land is now Washington Heights, of course. And yet, its commanding hilltop location, surrounded by tiny, lovely Roger Morris Park, offers a taste of the country to this day. The grounds burst with rosebushes and even include a small sunken garden. I could easily see going back just to sit there and read a book.

The mansion’s vast land holdings at one point stretched the (albeit pretty narrow that far north) width of Manhattan. All that land is now Washington Heights, of course. And yet, its commanding hilltop location, surrounded by tiny, lovely Roger Morris Park, offers a taste of the country to this day. The grounds burst with rosebushes and even include a small sunken garden. I could easily see going back just to sit there and read a book.

Who should visit the Morris-Jumel Mansion? Hamiltonians, for sure. Fans of old wallpaper, and fans of rich eccentric 19th century madames. Those into colonial architecture and house museums. The three house museums of upper Manhattan (Dyckman Farmhouse, here, and the Hamilton Grange) provide a varied look at life in the 18th and early 19th centuries. Visiting all three of them would make for a highly edifying afternoon.

For Reference:

| Address | Roger Morris Park, 65 Jumel Terrace, Manhattan |

|---|---|

| Website | morrisjumel.org |

| Cost | General Admission: $10 |

| Other Relevant Links |

|

BLDG 92 is the vowel-challenged, fascinating, historical center of the Brooklyn Navy Yard. It tells the story of the Navy Yard through artifacts, an interactive tabletop, and a comprehensive timeline.

BLDG 92 is the vowel-challenged, fascinating, historical center of the Brooklyn Navy Yard. It tells the story of the Navy Yard through artifacts, an interactive tabletop, and a comprehensive timeline.  Housed in a tiny storefront in Willamsburg, City Reliquary started as a hobby for its founder, who first created it as a display in a window in his apartment. It has grown from there as New Yorkers with collections of, well, whatever, occupied the space for exhibitions, and the Reliquary’s own collections multiplied.

Housed in a tiny storefront in Willamsburg, City Reliquary started as a hobby for its founder, who first created it as a display in a window in his apartment. It has grown from there as New Yorkers with collections of, well, whatever, occupied the space for exhibitions, and the Reliquary’s own collections multiplied. The current temporary show features perhaps the most under-appreciated of the city’s street foods, the humble knish. I learned things I never thought to wonder about knishes. Where they come from (the Eastern European knish belt extends from Latvia through Moldova); who makes them (there are six “Heroes of the Knish” who are the main local manufacturers); and what it means in Yiddish slang (lady parts). Also, back in 2013 Joan Rivers tweeted that Kim an Kanye should name their baby Knish because “who doesn’t love one?” Who knew?

The current temporary show features perhaps the most under-appreciated of the city’s street foods, the humble knish. I learned things I never thought to wonder about knishes. Where they come from (the Eastern European knish belt extends from Latvia through Moldova); who makes them (there are six “Heroes of the Knish” who are the main local manufacturers); and what it means in Yiddish slang (lady parts). Also, back in 2013 Joan Rivers tweeted that Kim an Kanye should name their baby Knish because “who doesn’t love one?” Who knew?

The current church is Gothic Revival, in brownstone, which always seems to me a striking and unlikely choice. Until this visit I never wondered what the surrounding area was like when it was built — if it was all brownstone rowhouses, it would’ve fit in nicely I suppose. Now it stands out, even as the surrounding skyscrapers far overtop it.

The current church is Gothic Revival, in brownstone, which always seems to me a striking and unlikely choice. Until this visit I never wondered what the surrounding area was like when it was built — if it was all brownstone rowhouses, it would’ve fit in nicely I suppose. Now it stands out, even as the surrounding skyscrapers far overtop it. Trinity’s history goes back to 1697, but this is the third church on this site. The first Trinity Church burned down in the Great Fire during the revolution in 1776. The second revealed structural problems following a severe snowstorm in 1838 that led to its replacement with the current building in 1846. So while it’s old, it’s not as old as it might want you to believe. St. Paul’s Chapel, a Trinity offshoot a short stroll north on Broadway, dates to 1766. I strongly recommend visiting both if you have time.

Trinity’s history goes back to 1697, but this is the third church on this site. The first Trinity Church burned down in the Great Fire during the revolution in 1776. The second revealed structural problems following a severe snowstorm in 1838 that led to its replacement with the current building in 1846. So while it’s old, it’s not as old as it might want you to believe. St. Paul’s Chapel, a Trinity offshoot a short stroll north on Broadway, dates to 1766. I strongly recommend visiting both if you have time. The interior of Trinity is pretty, but not especially noteworthy. It’s on a par with most other gothic revival churches in the U.S. or U.K.

The interior of Trinity is pretty, but not especially noteworthy. It’s on a par with most other gothic revival churches in the U.S. or U.K. Anyone who likes old churches or cemeteries or Hamilton (or Robert Fulton) must visit Trinity. Moreover, the graveyard is an oasis of green in a part of the city that doesn’t have a lot of that. For those frantically visiting all of Lower Manhattan’s many historic sites, museums, and other landmarks, it represents a chance to catch one’s breath in the midst of a jam-packed day. Trinity also has a fine music program–definitely take a look at their website. Even for a casual visitor, Trinity is worth a special trip.

Anyone who likes old churches or cemeteries or Hamilton (or Robert Fulton) must visit Trinity. Moreover, the graveyard is an oasis of green in a part of the city that doesn’t have a lot of that. For those frantically visiting all of Lower Manhattan’s many historic sites, museums, and other landmarks, it represents a chance to catch one’s breath in the midst of a jam-packed day. Trinity also has a fine music program–definitely take a look at their website. Even for a casual visitor, Trinity is worth a special trip.

Federal Hall is not what it seems. In fact, it’s not Federal Hall at all. From the outside a passer-by might easily believe that it was the first capitol of the U.S., and the building where George Washington took the oath as president. I thought that for years; only recently did I realize: right location, wrong building.

Federal Hall is not what it seems. In fact, it’s not Federal Hall at all. From the outside a passer-by might easily believe that it was the first capitol of the U.S., and the building where George Washington took the oath as president. I thought that for years; only recently did I realize: right location, wrong building.

But I couldn’t help get the sense that the National Park Service would trade today’s building if they could get the “real” Federal Hall back again.

But I couldn’t help get the sense that the National Park Service would trade today’s building if they could get the “real” Federal Hall back again.

The South Street Seaport Museum just celebrated its 50th anniversary, and its establishment contributed to the survival of a collection of historic buildings in the face of Lower Manhattan’s relentless pressure for development. The museum includes a print shop (worth visiting; great cards), the museum building proper, and the “street of ships,” a collection of historic vessels, several of which are open for tours when the museum is open.

The South Street Seaport Museum just celebrated its 50th anniversary, and its establishment contributed to the survival of a collection of historic buildings in the face of Lower Manhattan’s relentless pressure for development. The museum includes a print shop (worth visiting; great cards), the museum building proper, and the “street of ships,” a collection of historic vessels, several of which are open for tours when the museum is open.

Edgar Allan Poe, proto-goth, inventor of the detective story, writer of gruesome tales and horror-struck poetry, quother of the raven, had a hard life. Baltimore has largely claimed him as its own (just think of their NFL team). While he did live there for while, and died there in 1849, Poe was a New Yorker for a good chunk of his life. Indeed, he was only visiting Baltimore when he shuffled off his mortal coil in circumstances that remain mysterious to this day. For the last three years of his life Poe resided in a small rented cottage in what was then the village of Fordham in Westchester County, known today as the Bronx.

Edgar Allan Poe, proto-goth, inventor of the detective story, writer of gruesome tales and horror-struck poetry, quother of the raven, had a hard life. Baltimore has largely claimed him as its own (just think of their NFL team). While he did live there for while, and died there in 1849, Poe was a New Yorker for a good chunk of his life. Indeed, he was only visiting Baltimore when he shuffled off his mortal coil in circumstances that remain mysterious to this day. For the last three years of his life Poe resided in a small rented cottage in what was then the village of Fordham in Westchester County, known today as the Bronx. It’s furnished with a fair number of period pieces, three items of which are known to have been Poe’s: a rocking chair, a fancy gilded mirror, and the narrow bed where Virginia Poe passed away.

It’s furnished with a fair number of period pieces, three items of which are known to have been Poe’s: a rocking chair, a fancy gilded mirror, and the narrow bed where Virginia Poe passed away.

My guide during my visit was a local kid who really loved Poe and the place. His enthusiasm helped bring the cottage to life.

My guide during my visit was a local kid who really loved Poe and the place. His enthusiasm helped bring the cottage to life.

The African Burial Ground is a small monument overshadowed by the government buildings around Foley Square. As they were digging for a new federal building in 1991 they discovered bodies, and from there re-discovered a forgotten cemetery used by the city’s African American population in the late 1600s and early 1700s.

The African Burial Ground is a small monument overshadowed by the government buildings around Foley Square. As they were digging for a new federal building in 1991 they discovered bodies, and from there re-discovered a forgotten cemetery used by the city’s African American population in the late 1600s and early 1700s. Today a corner of what used to be the cemetery is a small green open space with a black granite monument, standing in for a headstone. There aren’t any markers, of course, and if it weren’t for the signs and a series of low humps of earth, you’d probably just think it was a pocket park. It’s not the whole extent of the cemetery, as this city is sufficiently about commerce and building that it won’t let the past fully forestall progress, even when that past includes the earthly remains of slaves.

Today a corner of what used to be the cemetery is a small green open space with a black granite monument, standing in for a headstone. There aren’t any markers, of course, and if it weren’t for the signs and a series of low humps of earth, you’d probably just think it was a pocket park. It’s not the whole extent of the cemetery, as this city is sufficiently about commerce and building that it won’t let the past fully forestall progress, even when that past includes the earthly remains of slaves.

The African Burial Ground is definitely not entertaining. But it is important. Every New Yorker and everyone with an interest in the city and its history should go and pay their respects.

The African Burial Ground is definitely not entertaining. But it is important. Every New Yorker and everyone with an interest in the city and its history should go and pay their respects. All the front windows of the house have neat, scary terra cotta faces centered above them. This was apparently a Dutch thing to ward off bad spirits. Reproductions are available at the gift shop!

All the front windows of the house have neat, scary terra cotta faces centered above them. This was apparently a Dutch thing to ward off bad spirits. Reproductions are available at the gift shop!

The Van Cortlandts in the early days were super-wealthy, and the house showed it. They were also super-Dutch, proud of their heritage as New Amsterdammers, and many of the details of the house (including a blue and orange color scheme for the china cabinets in the parlor) reflect that as well. Little that’s in the house today remains from the Van Cortlandts, but most of the publicly accessible rooms are filled with period furniture and knick-knacks that give a sense of what the lives of the earlier generations of the family might have been like.

The Van Cortlandts in the early days were super-wealthy, and the house showed it. They were also super-Dutch, proud of their heritage as New Amsterdammers, and many of the details of the house (including a blue and orange color scheme for the china cabinets in the parlor) reflect that as well. Little that’s in the house today remains from the Van Cortlandts, but most of the publicly accessible rooms are filled with period furniture and knick-knacks that give a sense of what the lives of the earlier generations of the family might have been like. When it opened as a museum, one room was redone to depict a modest city house, simulating how a much less successful Dutch family would have lived down in Manhattan. They’ve kept that to this day and while I would’ve liked the place to be as close as possible to how the family lived in it, the contrast is informative.

When it opened as a museum, one room was redone to depict a modest city house, simulating how a much less successful Dutch family would have lived down in Manhattan. They’ve kept that to this day and while I would’ve liked the place to be as close as possible to how the family lived in it, the contrast is informative.

The Van Cortlandts lived a very different kind of life than the

The Van Cortlandts lived a very different kind of life than the

The Museum of the City of New York is an absolute treasure. It occupies a really lovely Georgian/Federal-style building at the northern end of Museum Mile on Fifth Avenue. The Museum started out its life in

The Museum of the City of New York is an absolute treasure. It occupies a really lovely Georgian/Federal-style building at the northern end of Museum Mile on Fifth Avenue. The Museum started out its life in  For all that it’s merely fake old, it’s got one of the best staircases of any museum in the city, a super-elegant curve leading up from the ground floor. Nowadays complemented by a terrific light sculpture.

For all that it’s merely fake old, it’s got one of the best staircases of any museum in the city, a super-elegant curve leading up from the ground floor. Nowadays complemented by a terrific light sculpture.

on a rotating basis. Interact with a character and you get more, potentially much more, about them and their contribution. And it’s not just human characters, you can find out about players like beavers and oysters, too. I’m often skeptical of the value of these kinds of things. Too often they are more sizzle than steak. But this impressed me a lot.

on a rotating basis. Interact with a character and you get more, potentially much more, about them and their contribution. And it’s not just human characters, you can find out about players like beavers and oysters, too. I’m often skeptical of the value of these kinds of things. Too often they are more sizzle than steak. But this impressed me a lot.

And finally, as I do wherever I can, I will mention Alexander Hamilton, who is present, larger than life size, on the facade.

And finally, as I do wherever I can, I will mention Alexander Hamilton, who is present, larger than life size, on the facade.