| Edification value | |

|---|---|

| Entertainment value | |

| Should you go? | |

| Time spent | 62 minutes |

| Best thing I saw or learned |

This is the best, or at least weirdest, cabinet I have ever seen. Probably the most Gothic. And the least practical. An entire cathedral, tipped on its side! No putting that against the wall, that’s for sure.

|

UPDATE APRIL 2021: The Met has pulled the plug on its Breuer experiment, reducing its New York City empire to the classic mothership and The Cloisters. I liked what it was doing in the Breuer building, but the silver lining is the Frick is now playing in that space.

The first thing you should know about my take on the Met Breuer, housed in the former home of the Whitney Museum of American Art, is I really really really dislike the building. The iconic, Brutalist, Marcel Breuer art fortress says to me very loudly and in no uncertain terms, “Don’t come in here. You are not welcome.” It looms over the sidewalk. It has one big wonky window like Polyphemus’s eye. That’s it. It’s a Cyclopean building. A monster. Hide under a sheepskin on your way out or it’ll devour you.

You have to cross a narrow bridge over a crevasse to get in, upping the feeling of peril. Then once you’re in the lobby, the harsh concrete and spotlight-y lights feel like some kind of an art world police state, with you as the object of interrogation. “Admit it! Talk! You like MONET. Confess and maybe we’ll go easy on ya.”

One of the reasons I love the Whitney so much today is simply that it’s no longer in this building.

So, I have a bias.

The second thing you should know is, according to the Met, the architect’s name is pronounced BROY-er, not brewer. Just in case you wondered.

With the Whitney’s move to the Meatpacking District, naturally questions arose as to what to do with the Madison Avenue fortress. Fortunately (maybe?) the Met stepped in and leased it, making it the Met’s second satellite location after The Cloisters. Otherwise they probably would’ve turned it into an H&M or a fancy food hall or something.

Thus far, the Met has used the Breuer building to…well, to let its institutional hair down a bit, it seems. None of the permanent collection has moved. Rather, it leverages the space for special exhibitions. They tend to the modern or contemporary, which is good given the space. And yet, the Met’s also done some fairly fascinating surveys, leveraging the strength of its encyclopedic collection but doing things they might not want to do, or even be able to do, in any of the spaces in the mother ship on Fifth Avenue.

When I visited, one show consisted of four video installations, which were okay. Certainly video works well in the cavelike Breuer space.

Ettore Sottsass, Design Maverick

The other show, on the designer Ettore Sottsass, exemplifies what I mean about letting the Met go a little bonkers installation-wise.

Sottsass first found fame designing an iconic Olivetti portable manual typewriter, in super-sexy lipstick red, with a case that could double as a waste-paper basket. It’s adorable and brilliant, and the Met shows it off alongside other modern designs meant to be cheap and cheerful, like a One Laptop Per Child laptop.

But on top of that, they introduce it with a…colorful quote from Sottsass. I have been visiting the Met for over 20 years, and I really don’t think I’ve ever seen that word in a wall text there before, much less in big type as a key quote.

Sottsass had a long career designing things of all types, including the outdoor furniture that uses classical capitals and columns in the photo above. This also provides a typical view of Met Breuer gallery space, with its slate floors and the waffle iron ceiling.

Ettore Sottsass also went on to found the short-lived, exuberant, 1980s “Memphis” design movement, exemplified by his wacky, colorful room divider here.

Creativity Unleashed

Cleverly, the Met juxtaposed some chunky Memphis jewelry with 4,000 year old Egyptian pieces (that looked really good by comparison). They did things like that throughout. Sottsass designed some glass art pieces he called “Kachinas,” and the Met displayed them next to Hopi dolls from its collection. They displayed some of Sotsass’s nifty, colorful, tall, ceramic towers with a Frank Lloyd Wright architectural model, some Shiva Lingam, and a Chinese jade Neolithic ritual object. Throughout the show, these sorts of unexpected pairings helped illuminate Sottsass’s work, providing a look at objects that might have inspired him, or at least creating a novel context for his pieces. I really enjoyed it.

Creative combinations of works in a dialogue across thousands of years and diverse cultures is something places like the Brooklyn Museum have been trying for some time, not always successfully. The Met seems to be using the Breuer to experiment with that approach to curating a show. And I think they’re doing it really well so far.

My Bottom Line on the Met Breuer

So what’s my bottom line on the Met Breuer? I’m not going to say everyone should drop everything and go. The building might be interesting, but I still don’t think it’s a welcoming or pleasant place to see art. But I can’t deny the creativity that’s going into the Met’s programming at the Met Breuer. The staff has done some tremendous shows there so far, full of…spirit. If having the Breuer lets them think about their collection in novel ways, and tell new stories about art, I value that highly. Hopefully some of the Met Breuer spirit will eventually find outlets in the Fifth Avenue HQ, too.

For Reference:

| Address | 945 Madison Avenue, (at East 75th Street) Manhattan |

|---|---|

| Website | metmuseum.org/visit/met-breuer |

| Cost | General Admission: $25 (Suggested) |

SculptureCenter, a museum dedicated to, yes, sculpture, resides in an historic old trolley garage in the eye of the gentrification storm that is Long Island City these days. The stroll there from the Queensboro Plaza subway station boggles the mind — new residential high rises seem to be sprouting on every single lot for blocks around.

SculptureCenter, a museum dedicated to, yes, sculpture, resides in an historic old trolley garage in the eye of the gentrification storm that is Long Island City these days. The stroll there from the Queensboro Plaza subway station boggles the mind — new residential high rises seem to be sprouting on every single lot for blocks around. A pair of Christian Louboutin boots laboriously decorated with antique glass beads by Jamie Okuma, of the Louiseño and Shoshone-Bannock tribes.

A pair of Christian Louboutin boots laboriously decorated with antique glass beads by Jamie Okuma, of the Louiseño and Shoshone-Bannock tribes. The National Museum of the American Indian’s George Gustav Heye Center is one of the Smithsonian Institution’s two New York outposts (along with the

The National Museum of the American Indian’s George Gustav Heye Center is one of the Smithsonian Institution’s two New York outposts (along with the

Indeed, the idea of turning a building focused on trade, from an era that unabashedly glorified the commercial impulses that ended up dispossessing the Native American tribes of their lands, into a museum for those nations…well. I find it pretty ironic.

Indeed, the idea of turning a building focused on trade, from an era that unabashedly glorified the commercial impulses that ended up dispossessing the Native American tribes of their lands, into a museum for those nations…well. I find it pretty ironic.

The surveillance show undermines its cautionary purpose by outlining a lot of frankly very silly spying technologies developed over the years. The CIA apparently spent $15m trying to surgically wire a feline for sound, to approach and unobtrusively listen to conversations. Sadly, “Acoustic Kitty” failed by being run over by a taxi on its first test deployment. Truly cat-astrophic.

The surveillance show undermines its cautionary purpose by outlining a lot of frankly very silly spying technologies developed over the years. The CIA apparently spent $15m trying to surgically wire a feline for sound, to approach and unobtrusively listen to conversations. Sadly, “Acoustic Kitty” failed by being run over by a taxi on its first test deployment. Truly cat-astrophic. There were once 49 armories and arsenals in the Naked City (according to

There were once 49 armories and arsenals in the Naked City (according to

Max Vityk’s “Outcrops” series of tactile, colorful, geologic abstract paintings installed in the third floor library and dining room. Sometimes abstract art clashes with classical decor, but these go better than they have any right to. Compliments to the curator for a beautiful installation.

Max Vityk’s “Outcrops” series of tactile, colorful, geologic abstract paintings installed in the third floor library and dining room. Sometimes abstract art clashes with classical decor, but these go better than they have any right to. Compliments to the curator for a beautiful installation.

First Floor: A brief introduction to Ukraine, the place, its people, history and culture. It includes a nice touchscreen display for those who want a deeper dive, and an overview of notable Ukrainian Americans.

First Floor: A brief introduction to Ukraine, the place, its people, history and culture. It includes a nice touchscreen display for those who want a deeper dive, and an overview of notable Ukrainian Americans.

The Brooklyn Historical Society’s gorgeousness struck me throughout — a very loving restoration must have happened here in the not-too-distant past. The light fixtures! The woodwork! The stained glass skylight! And each floor had different humorously old-timey logos indicating where the gents and ladies rooms were. A small thing, but I appreciated it.

The Brooklyn Historical Society’s gorgeousness struck me throughout — a very loving restoration must have happened here in the not-too-distant past. The light fixtures! The woodwork! The stained glass skylight! And each floor had different humorously old-timey logos indicating where the gents and ladies rooms were. A small thing, but I appreciated it.

A juxtaposition of two pieces: My Egypt, by Charles Demuth, and Pittsburgh, by Elsie Driggs. Both from 1927, they present similar and yet extremely divergent visions of industrialized landscapes. One is clearly prettier than the other, and yet, as Driggs said of her grey smokestacks and pipes, “This shouldn’t be beautiful. But it is.”

A juxtaposition of two pieces: My Egypt, by Charles Demuth, and Pittsburgh, by Elsie Driggs. Both from 1927, they present similar and yet extremely divergent visions of industrialized landscapes. One is clearly prettier than the other, and yet, as Driggs said of her grey smokestacks and pipes, “This shouldn’t be beautiful. But it is.”

Kaisik Wong’s spacey, glam 1970s fashions look like costumes from a very trippy sci-fi film. The opposite of most of the counterculture fashion on display, and yet they fit in somehow, too.

Kaisik Wong’s spacey, glam 1970s fashions look like costumes from a very trippy sci-fi film. The opposite of most of the counterculture fashion on display, and yet they fit in somehow, too. New York City is lucky to boast not one but two extremely fine design museums — the Museum of Arts and Design and the

New York City is lucky to boast not one but two extremely fine design museums — the Museum of Arts and Design and the  When they laid the cornerstone for the Music Hall, Andrew Carnegie himself said that “here all good causes may find a platform.” Remarkably, that statement evolved into a policy of openness to anyone who wanted to take the stage (and could afford to rent it). So even in times when many venues were closed to, say, African American performers, Carnegie was open.

When they laid the cornerstone for the Music Hall, Andrew Carnegie himself said that “here all good causes may find a platform.” Remarkably, that statement evolved into a policy of openness to anyone who wanted to take the stage (and could afford to rent it). So even in times when many venues were closed to, say, African American performers, Carnegie was open. The Rose Museum is a small space telling the story of Carnegie Hall, twice actually: once from a building/Carnegie perspective, the other more from an artistic perspective. But they run together and get a little redundant. It is indeed between the auditorium and the First Tier restrooms, as well as the patrons’ lounge.

The Rose Museum is a small space telling the story of Carnegie Hall, twice actually: once from a building/Carnegie perspective, the other more from an artistic perspective. But they run together and get a little redundant. It is indeed between the auditorium and the First Tier restrooms, as well as the patrons’ lounge.

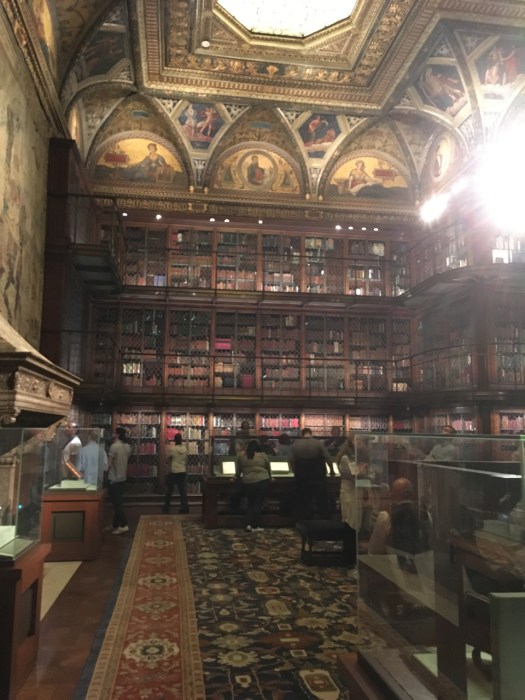

The West Room Vault, which Charles McKim designed so that Mr. Morgan could keep his most super-special books super safe.

The West Room Vault, which Charles McKim designed so that Mr. Morgan could keep his most super-special books super safe. Many of the city’s great institutions, maybe even most of them, were gifts to the public by plutocrats looking to give something back, improve their image, or maybe atone for awful things they did to get ahead. Fro some people, it may diminish the joy of visiting somewhat to reflect on the ruthless profiteering that paid for all of it. That’s especially true of the most personality-driven institutions, like the Morgan and the Frick.

Many of the city’s great institutions, maybe even most of them, were gifts to the public by plutocrats looking to give something back, improve their image, or maybe atone for awful things they did to get ahead. Fro some people, it may diminish the joy of visiting somewhat to reflect on the ruthless profiteering that paid for all of it. That’s especially true of the most personality-driven institutions, like the Morgan and the Frick.

I love how the Morgan smells. The parts that are more library than museum contain enough ancient tomes that the very air is permeated with old leather, paper, and erudition.

I love how the Morgan smells. The parts that are more library than museum contain enough ancient tomes that the very air is permeated with old leather, paper, and erudition.