| Edification value | |

|---|---|

| Entertainment value | |

| Should you go? | |

| Time spent | 45 minutes |

| Best thing I saw or learned | It can be hard for an untrained modern viewer to distinguish between youths and women in Japanese prints. There are subtle but important hairstyle and fabric differences but in terms of face and body shape, they were depicted very similarly. I wonder how many pretty women I’ve seen in woodblock prints over the years have actually been pretty dudes. |

The Japan Society’s home, Japan House, was designed in 1971, by architects Junzo Yoshimura and George Shimamoto of Gruzen & Partners, and built on a site near the United Nations donated by the Society’s then-president, John D. Rockefeller the Third. The Society’s history, however, goes back much further than that; it was founded in 1907 in the wake of an official U.S. visit by two Japanese dignitaries. Its fortunes have waxed and waned along with Japan-U.S. relations, and today the society is a great place to take a language class, hear a talk, see a movie, or see some art.

The Japan Society’s home, Japan House, was designed in 1971, by architects Junzo Yoshimura and George Shimamoto of Gruzen & Partners, and built on a site near the United Nations donated by the Society’s then-president, John D. Rockefeller the Third. The Society’s history, however, goes back much further than that; it was founded in 1907 in the wake of an official U.S. visit by two Japanese dignitaries. Its fortunes have waxed and waned along with Japan-U.S. relations, and today the society is a great place to take a language class, hear a talk, see a movie, or see some art.

The building feels simultaneously modern (for a midcentury architectural definition of same) and Japanese, and the first thing you notice on entering is the sound of water from a gentle fountain, replete with a stand of bamboo, a modernist, completely enclosed and skylit, take on a traditional courtyard garden.

The Society’s gallery space is on the second floor, in rooms arrayed around the courtyard. They program all kinds of stuff there. It’s one of the first places I saw Haruki Murakami’s work; they’ve done great shows on crafts like contemporary Japanese basketwaving and ceramics; they did a show a couple of years ago on cats in Japanese art (I bet the Brooklyn curators were jealous the Japan Society thought of it first)… It’s a broad and varied list, always tied back to Japan.

The Society’s gallery space is on the second floor, in rooms arrayed around the courtyard. They program all kinds of stuff there. It’s one of the first places I saw Haruki Murakami’s work; they’ve done great shows on crafts like contemporary Japanese basketwaving and ceramics; they did a show a couple of years ago on cats in Japanese art (I bet the Brooklyn curators were jealous the Japan Society thought of it first)… It’s a broad and varied list, always tied back to Japan.

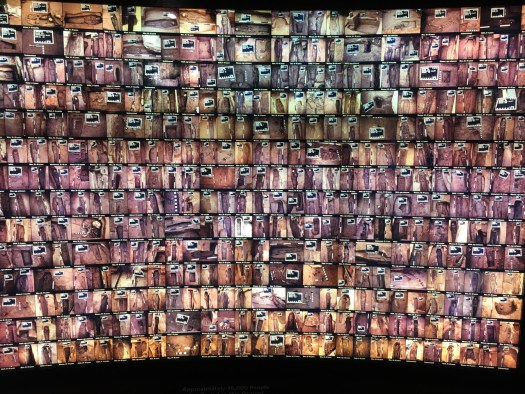

The current show is called A Third Gender: Beautiful Youths in Japanese Prints, and looks at societal impressions of essentially tween- and teenage boys in early modern Japan. It makes the case that they were viewed as beautiful and desirable by both men and women, and displays a variety of contemporary woodblock prints, books, and other artifacts to examine how they were depicted and described in that society.

The current show is called A Third Gender: Beautiful Youths in Japanese Prints, and looks at societal impressions of essentially tween- and teenage boys in early modern Japan. It makes the case that they were viewed as beautiful and desirable by both men and women, and displays a variety of contemporary woodblock prints, books, and other artifacts to examine how they were depicted and described in that society.

I am emphatically not going to use this blog to discuss concepts of gender or the politics of sexuality. But I was disturbed by this exhibition, because it robs the subject of the show of all agency: there’s nothing in it that says whether tween and teen boys in Japan liked being or wanted to be the objects of lustful attentions from grown up men and women. To me it feels uncomfortably like looking at TV shows and advertising from 1950s and 1960s America and concluding that women then enjoyed being secretaries and housewives and having their butts pinched by the boss.

My misgivings aside, like all Japan Society exhibitions I’ve attended it was well curated and thoughtfully designed. While none of the pieces in it is super-famous or a masterpiece, it leverages depth of collection to examine an otherwise unknown facet of life in Tokugawa Era (ca 1600-1868) Japan.

Unless you’re a fan of the Land of the Rising Sun (full disclosure, I am a fan, and have been a member of the Japan Society for well over a decade) I don’t think the Japan Society generally merits a special trip to the far eastern reaches of midtown Manhattan. But they put on a good show, and if you happen to be by the United Nations it’s an excellent place to imbibe some culture that will almost certainly be beautiful and interesting.

Unless you’re a fan of the Land of the Rising Sun (full disclosure, I am a fan, and have been a member of the Japan Society for well over a decade) I don’t think the Japan Society generally merits a special trip to the far eastern reaches of midtown Manhattan. But they put on a good show, and if you happen to be by the United Nations it’s an excellent place to imbibe some culture that will almost certainly be beautiful and interesting.

For Reference:

| Address | 333 E 47th Street, Manhattan |

|---|---|

| Website | japansociety.org |

| Cost | General Admission: $12 |

| Other Relevant Links |

|

The African Burial Ground is a small monument overshadowed by the government buildings around Foley Square. As they were digging for a new federal building in 1991 they discovered bodies, and from there re-discovered a forgotten cemetery used by the city’s African American population in the late 1600s and early 1700s.

The African Burial Ground is a small monument overshadowed by the government buildings around Foley Square. As they were digging for a new federal building in 1991 they discovered bodies, and from there re-discovered a forgotten cemetery used by the city’s African American population in the late 1600s and early 1700s. Today a corner of what used to be the cemetery is a small green open space with a black granite monument, standing in for a headstone. There aren’t any markers, of course, and if it weren’t for the signs and a series of low humps of earth, you’d probably just think it was a pocket park. It’s not the whole extent of the cemetery, as this city is sufficiently about commerce and building that it won’t let the past fully forestall progress, even when that past includes the earthly remains of slaves.

Today a corner of what used to be the cemetery is a small green open space with a black granite monument, standing in for a headstone. There aren’t any markers, of course, and if it weren’t for the signs and a series of low humps of earth, you’d probably just think it was a pocket park. It’s not the whole extent of the cemetery, as this city is sufficiently about commerce and building that it won’t let the past fully forestall progress, even when that past includes the earthly remains of slaves.

The African Burial Ground is definitely not entertaining. But it is important. Every New Yorker and everyone with an interest in the city and its history should go and pay their respects.

The African Burial Ground is definitely not entertaining. But it is important. Every New Yorker and everyone with an interest in the city and its history should go and pay their respects. Utterly unsurprisingly, there were four references to Michelle Obama in the text for the Black Fashion Designers show. Because I really miss having her in the White House, I’ll pick the Laura Smalls sundress Mrs. Obama wore on Carpool Karaoke.

Utterly unsurprisingly, there were four references to Michelle Obama in the text for the Black Fashion Designers show. Because I really miss having her in the White House, I’ll pick the Laura Smalls sundress Mrs. Obama wore on Carpool Karaoke. If I think about the Fashion Institute of Technology (FIT), it’s generally in terms of the building — the brutalist concrete pile that jumps over 27th Street at 7th Avenue, the anchor tenant of the Garment District. I’ve walked by it many times and surely I’ve seen the sign that said “museum” — it’s pretty evident. But not being especially a part of that world, I probably just glossed over it, edited it out, walked on. The Museum Project ensures that doesn’t happen anymore. My museum-dar is now top-notch.

If I think about the Fashion Institute of Technology (FIT), it’s generally in terms of the building — the brutalist concrete pile that jumps over 27th Street at 7th Avenue, the anchor tenant of the Garment District. I’ve walked by it many times and surely I’ve seen the sign that said “museum” — it’s pretty evident. But not being especially a part of that world, I probably just glossed over it, edited it out, walked on. The Museum Project ensures that doesn’t happen anymore. My museum-dar is now top-notch.

Through a door, the second room opened upward and outward, to about triple height, a real surprise given the subterranean location. Again black, but this was a wide-open, encompassing space filled, tastefully and carefully, with islands of beautifully dressed mannequins stretching into the distance. “Zou bisou bisou” (but not the Mad Men version) playing in the background quietly set the tone. I’ve discovered I like museums that use music subtly and cleverly to set a tone or convey a time. Here it works particularly well.

Through a door, the second room opened upward and outward, to about triple height, a real surprise given the subterranean location. Again black, but this was a wide-open, encompassing space filled, tastefully and carefully, with islands of beautifully dressed mannequins stretching into the distance. “Zou bisou bisou” (but not the Mad Men version) playing in the background quietly set the tone. I’ve discovered I like museums that use music subtly and cleverly to set a tone or convey a time. Here it works particularly well. I didn’t spend a lot of time at the Museum at FIT, but that was mainly because I had a meeting to get to. Even with my fairly limited knowledge of and interest in clothing, I could’ve spent another 15 or 20 minutes. Both shows were expertly and lovingly curated and beautifully presented. I have no doubt that FIT has the resources to deliver an authoritative exhibition on any fashionable topic it cares to. And both exhibits zoomed in on subjects that the Met Fashion Institute, with its more general audience, probably wouldn’t do.

I didn’t spend a lot of time at the Museum at FIT, but that was mainly because I had a meeting to get to. Even with my fairly limited knowledge of and interest in clothing, I could’ve spent another 15 or 20 minutes. Both shows were expertly and lovingly curated and beautifully presented. I have no doubt that FIT has the resources to deliver an authoritative exhibition on any fashionable topic it cares to. And both exhibits zoomed in on subjects that the Met Fashion Institute, with its more general audience, probably wouldn’t do.

I wasn’t sure what to expect from the Museum of Chinese in America (MOCA for short). I knew the space would be great — it was designed by Maya Lin. But having recently been a bit disappointed by

I wasn’t sure what to expect from the Museum of Chinese in America (MOCA for short). I knew the space would be great — it was designed by Maya Lin. But having recently been a bit disappointed by  MOCA is indeed a beautifully designed museum. The space is consists of a series of rooms that surround a central open atrium, which extends from a skylight down to the classrooms, office, and restrooms on the basement level. Scarred bare brick underscores the age of the building, and its more industrial heritage. And windows carved into the rooms around the atrium ensure there’s always some natural light filtering in. The windows aren’t just openings, though: videos projected onto them make them serve a very clever dual purpose — the videos are also visible, of course, from the atrium side of the glass as well.

MOCA is indeed a beautifully designed museum. The space is consists of a series of rooms that surround a central open atrium, which extends from a skylight down to the classrooms, office, and restrooms on the basement level. Scarred bare brick underscores the age of the building, and its more industrial heritage. And windows carved into the rooms around the atrium ensure there’s always some natural light filtering in. The windows aren’t just openings, though: videos projected onto them make them serve a very clever dual purpose — the videos are also visible, of course, from the atrium side of the glass as well. The educational program succeeds as well as the building does. MOCA does exactly what you’d expect: tells the story of the Chinese immigrant experience in the United States. The show is largely chronological, starting with Chinese immigration to build the railroads and the subsequent racist reactions to Chinese immigration in the 19th century, which led to laws that essentially prevented most Chinese immigration, as well as constraining the kinds of work Chinese immigrants could do.

The educational program succeeds as well as the building does. MOCA does exactly what you’d expect: tells the story of the Chinese immigrant experience in the United States. The show is largely chronological, starting with Chinese immigration to build the railroads and the subsequent racist reactions to Chinese immigration in the 19th century, which led to laws that essentially prevented most Chinese immigration, as well as constraining the kinds of work Chinese immigrants could do.

In addition to the main space, there are two areas for temporary exhibitions. They currently feature an awesome look at Chinese food in the US, featuring about 33 chefs. Wall projections show video interviews where they speak about their lives and work and their take on “authenticity.” The museum set up one room like a banquet, with place settings for each chef that includes a short bio. This is a missed opportunity in our photogenic food-obsessed instagram age: there should be pictures of each chef’s signature dish at their setting. Still it’s a fun show, including a collection of personally meaningful objects: cleavers, cutting boards, menus, and such. Martin Yan’s wok is there, and Danny Bowien’s favorite spoon.

In addition to the main space, there are two areas for temporary exhibitions. They currently feature an awesome look at Chinese food in the US, featuring about 33 chefs. Wall projections show video interviews where they speak about their lives and work and their take on “authenticity.” The museum set up one room like a banquet, with place settings for each chef that includes a short bio. This is a missed opportunity in our photogenic food-obsessed instagram age: there should be pictures of each chef’s signature dish at their setting. Still it’s a fun show, including a collection of personally meaningful objects: cleavers, cutting boards, menus, and such. Martin Yan’s wok is there, and Danny Bowien’s favorite spoon.

El Museo del Barrio is currently the northernmost of the “Museum Mile” museums, occupying a stately building on Fifth Avenue, just across 104th Street from the Museum of the City of New York. According to its website, it started in the early 1970s as a cultural center focused on Puerto Rico. It has since expanded its focus to cover all Latin American and Caribbean art and artists. After bouncing around East Harlem a bit it found its current home in the Heckscher Building in 1977.

El Museo del Barrio is currently the northernmost of the “Museum Mile” museums, occupying a stately building on Fifth Avenue, just across 104th Street from the Museum of the City of New York. According to its website, it started in the early 1970s as a cultural center focused on Puerto Rico. It has since expanded its focus to cover all Latin American and Caribbean art and artists. After bouncing around East Harlem a bit it found its current home in the Heckscher Building in 1977. The main show when I visited was of video art by Beatriz Santiago Muñoz, as well as selections she chose from the museum’s permanent collection. I run hot and cold with video art. On the one hand, two of the best, most memorable works of art I’ve seen in the past two years were video pieces. On the other hand, I am bored to tears with the vast majority of it. Muñoz’s work, largely non-narrative, did little for me. I lacked the eye or knowledge to understand how her selections from the permanent collection clicked with what she’s trying to do.

The main show when I visited was of video art by Beatriz Santiago Muñoz, as well as selections she chose from the museum’s permanent collection. I run hot and cold with video art. On the one hand, two of the best, most memorable works of art I’ve seen in the past two years were video pieces. On the other hand, I am bored to tears with the vast majority of it. Muñoz’s work, largely non-narrative, did little for me. I lacked the eye or knowledge to understand how her selections from the permanent collection clicked with what she’s trying to do. The other show featured recent acquisitions, definitely a common and valid theme for a museum, although given the small space available, I didn’t find it very edifying as far as key current trends in Latin or Caribbean art. I liked some of the pieces, but I also thought much of the work on view wasn’t especially “Latin.”

The other show featured recent acquisitions, definitely a common and valid theme for a museum, although given the small space available, I didn’t find it very edifying as far as key current trends in Latin or Caribbean art. I liked some of the pieces, but I also thought much of the work on view wasn’t especially “Latin.”

Without a doubt the Onassis Center was good for my vocabulary (which is very good to begin with). I picked up six new-to-me words, at least five of which I am sure I will find opportunities to use in the near future.

Without a doubt the Onassis Center was good for my vocabulary (which is very good to begin with). I picked up six new-to-me words, at least five of which I am sure I will find opportunities to use in the near future.

The Museum of the City of New York is an absolute treasure. It occupies a really lovely Georgian/Federal-style building at the northern end of Museum Mile on Fifth Avenue. The Museum started out its life in

The Museum of the City of New York is an absolute treasure. It occupies a really lovely Georgian/Federal-style building at the northern end of Museum Mile on Fifth Avenue. The Museum started out its life in  For all that it’s merely fake old, it’s got one of the best staircases of any museum in the city, a super-elegant curve leading up from the ground floor. Nowadays complemented by a terrific light sculpture.

For all that it’s merely fake old, it’s got one of the best staircases of any museum in the city, a super-elegant curve leading up from the ground floor. Nowadays complemented by a terrific light sculpture.

on a rotating basis. Interact with a character and you get more, potentially much more, about them and their contribution. And it’s not just human characters, you can find out about players like beavers and oysters, too. I’m often skeptical of the value of these kinds of things. Too often they are more sizzle than steak. But this impressed me a lot.

on a rotating basis. Interact with a character and you get more, potentially much more, about them and their contribution. And it’s not just human characters, you can find out about players like beavers and oysters, too. I’m often skeptical of the value of these kinds of things. Too often they are more sizzle than steak. But this impressed me a lot.

And finally, as I do wherever I can, I will mention Alexander Hamilton, who is present, larger than life size, on the facade.

And finally, as I do wherever I can, I will mention Alexander Hamilton, who is present, larger than life size, on the facade.

This incredible 1872 punch bowl and goblets, 36 pieces and 800 ounces worth (that’s 50 pounds! 22.68kg!) of sterling silver. A gift to Isaac Newton Marks, president of the New Orleans Fireman’s Charitable Association. It’s hard to see in the picture but the stem of each goblet is a fire fighter.

This incredible 1872 punch bowl and goblets, 36 pieces and 800 ounces worth (that’s 50 pounds! 22.68kg!) of sterling silver. A gift to Isaac Newton Marks, president of the New Orleans Fireman’s Charitable Association. It’s hard to see in the picture but the stem of each goblet is a fire fighter. The Fire Museum is like the attic of the New York City Fire Department. It’s where all the old interesting stuff is, and exploring it is very much like sifting through a collection of fire-related artifacts that someone at some point considered worth keeping.

The Fire Museum is like the attic of the New York City Fire Department. It’s where all the old interesting stuff is, and exploring it is very much like sifting through a collection of fire-related artifacts that someone at some point considered worth keeping.  In addition to coins, the Numismatic Society has some paper money, including this 1855 Bank of NY note. It’s been a while since I heard the phrase “queer as a three dollar bill” but I never thought I’d actually see one.

In addition to coins, the Numismatic Society has some paper money, including this 1855 Bank of NY note. It’s been a while since I heard the phrase “queer as a three dollar bill” but I never thought I’d actually see one. The American Numismatic Society is the center for all things related to the world of coins and coin collecting. Their offices in Tribeca are literally a vault, with a heavily secured air lock-style entry way. There’s a noticeable difference in air pressure when you go in, too.

The American Numismatic Society is the center for all things related to the world of coins and coin collecting. Their offices in Tribeca are literally a vault, with a heavily secured air lock-style entry way. There’s a noticeable difference in air pressure when you go in, too.