| Edification value | |

|---|---|

| Entertainment value | |

| Should you go? | |

| Time spent | 38 minutes |

| Best thing I saw or learned |  Baby Bootlegger was a 1924, 29-foot 10-inch speedboat with a 240 horsepower engine. She was designed by George F. Crouch, built by Henry B. Nevins of City Island, and owned by Caleb Bragg. She won the Gold Cup in 1924 and 1925 and I’m sure no rum was ever run in her. Baby Bootlegger was a 1924, 29-foot 10-inch speedboat with a 240 horsepower engine. She was designed by George F. Crouch, built by Henry B. Nevins of City Island, and owned by Caleb Bragg. She won the Gold Cup in 1924 and 1925 and I’m sure no rum was ever run in her. |

Misnomer Island

“New York” conjures very specific images. Possibly positive, possibly negative, but distinctive, and related to density, height, congestion, diversity, and creativity. Extremes of wealth and poverty. And yet New York also contains neighborhoods that feel nothing like “New York.”

The City Island Nautical Museum aims to tell the story of arguably the least “New York” place in all of New York City. Despite its misleading name, City Island does not feel “city” in any way. Rather, it’s a quiet village, whose heritage and livelihood has long focused on the waters of Long Island Sound.

City Island was part of the massive tract of land ceded by the Lenape to Thomas Pell (whose story the Bartow-Pell Mansion recounts) in 1654. It developed into a fairly self-sufficient seagoing community. Oystering supported City Islanders for many years, until the oysters ran out. And boatbuilding was a massive industry. Eight America’s Cup winning yachts were built at City Island from 1870-1980. And they built mine sweepers there during World War II.

Today, sailors still have reason to go — it’s home to some five yacht clubs. But for most New Yorkers, City Island barely registers in their consciousness, except as a curious, far-flung corner of the city.

A Schoolhouse Full of Stuff

The City Island Nautical Museum occupies the island’s old schoolhouse. Its four rooms each focus on a specific theme:

- the School Room, focused on the island’s schools and kids who went there;

- the Nautical Room, on boats and boatbuilding;

- the Community Room, on life on City Island from pre-colonial days to now; and

- the Library.

In addition to various books, copies of Yachting magazine going back to the 1930s, and neat ship models, the library currently houses a temporary show of local artwork memorializing the City Island Bridge, recently torn down.

In addition to various books, copies of Yachting magazine going back to the 1930s, and neat ship models, the library currently houses a temporary show of local artwork memorializing the City Island Bridge, recently torn down.

A Charming But Chaotic Collection

I’d call this museum “charming,” if I’m feeling charitable, and “chaotic” if I’m feeling less so. It’s a bit of both. This is a museum by accretion, like the Maritime Industry Museum.

But the Maritime Industry Museum is a paragon of military-grade organization. It’s dense but not dusty, its artifacts are well cared for, and you know every object there has been carefully cataloged.

By contrast, the City Island Museum is a hodge-podge. Things on display aren’t always in good repair. It feels like the museum may not even know all that it has. And that’s sort of a shame.

Then again, I have to say much of the collection feels random and not very important. For example, the museum has an array of outboard motors that look like they date to the 1940s-1960s. Whose outboard motors were they? Are they historically important for some reason? Who made them and why? There’s a case of arrowheads. A bunch of old bottles. Old cameras. Nothing feels…documented. The artifacts kind of tell a City Island story, in that they all presumably were used there at some point. But they don’t tell it in coherently. And they crowd out things that would give a better understanding of the island’s people and times.

Then again, I have to say much of the collection feels random and not very important. For example, the museum has an array of outboard motors that look like they date to the 1940s-1960s. Whose outboard motors were they? Are they historically important for some reason? Who made them and why? There’s a case of arrowheads. A bunch of old bottles. Old cameras. Nothing feels…documented. The artifacts kind of tell a City Island story, in that they all presumably were used there at some point. But they don’t tell it in coherently. And they crowd out things that would give a better understanding of the island’s people and times.

Stories I wish the City Island Museum told:

- City Island’s days as a weekend getaway — it used to have public beaches and an easier connection to the city. Could it have become a northern Coney Island?

- The short-lived, dangerous City Island Monorail (amazing story; see the Bowery Boys link in the box at the end of this review).

- The changing population and demographics of the island. Who lives there now?

- Early ambitions for City Island — the name comes from a bout of marketing optimism that it’d someday rival New York as a maritime port.

Should You Visit?

Like the Old Stone House, this museum isn’t really for tourists. Or, it’s only partly for tourists. It’s a center for the community, a place where people can come and research family ties to the island, and a place where clam diggers (i.e., native City Islanders; the rest of us are “mussel suckers”) can contribute bits of their own legacies to be part of the greater story.

You should go to City Island, unquestionably. It’s unique in New York. And if you go, to sail, to just look around, or to have a piña colada at Johnny’s Reef Restaurant (which I personally recommend) then, sure, stop in at the City Island Nautical Museum. It’s a thing to do. But I would not recommend planning a trip to the island just to visit this small, charming but too-chaotic museum.

For Reference:

| Address | 190 Fordham Street, City Island |

|---|---|

| Website | cityislandmuseum.org |

| Cost | General Admission: $5 |

| Other Relevant Links |

Long ago (1654) and far away (under an oak tree on what is now the frontier of the Bronx), a, Englishman named Thomas Pell signed a treaty with the local Siwanoy/ Lenape Indian tribe. He gained ownership of either 9,166 acres (City of New York, Friends of Pelham Bay Park, other reputable sources) or 50,000 acres (Bartow-Pell Mansion printout, Wikipedia) of land. While his descendants sold off the massive holding over time, in 1836 Robert Bartow, scion of the Bartow-Pell family, bought back part of the original estate and started building a fine country house and working farm on it. In 1842, he and his wife Maria Lorillard Bartow, their seven kids, and assorted Irish servants moved out from the filth and hubbub of New York City. The family resided there for over 40 years.

Long ago (1654) and far away (under an oak tree on what is now the frontier of the Bronx), a, Englishman named Thomas Pell signed a treaty with the local Siwanoy/ Lenape Indian tribe. He gained ownership of either 9,166 acres (City of New York, Friends of Pelham Bay Park, other reputable sources) or 50,000 acres (Bartow-Pell Mansion printout, Wikipedia) of land. While his descendants sold off the massive holding over time, in 1836 Robert Bartow, scion of the Bartow-Pell family, bought back part of the original estate and started building a fine country house and working farm on it. In 1842, he and his wife Maria Lorillard Bartow, their seven kids, and assorted Irish servants moved out from the filth and hubbub of New York City. The family resided there for over 40 years.

The first time I visited the Jewish Museum, in July of 2017, it was in the midst of re-installing its permanent collection, taking a floor and a substantial part of the reason to visit offline. I had doubts concerning the temporary shows on at the time— odd curatorial decisions, highly esoteric subject matter and general kitschiness all nudged me away from strongly recommending the museum.

The first time I visited the Jewish Museum, in July of 2017, it was in the midst of re-installing its permanent collection, taking a floor and a substantial part of the reason to visit offline. I had doubts concerning the temporary shows on at the time— odd curatorial decisions, highly esoteric subject matter and general kitschiness all nudged me away from strongly recommending the museum. A scale model of the Brooklyn Navy Yard in full swing during World War II. I can only imagine the hours and focus and attention it required YNC Leo J. Spiegel USN (Ret.) to build it. Scaled at 1 inch = 50 feet, it depicts 46 naval vessels (all called out by name on a sign below), 273 shipyard buildings, 8 piers, 6 drydocks, and 659 homes in the surrounding area.

A scale model of the Brooklyn Navy Yard in full swing during World War II. I can only imagine the hours and focus and attention it required YNC Leo J. Spiegel USN (Ret.) to build it. Scaled at 1 inch = 50 feet, it depicts 46 naval vessels (all called out by name on a sign below), 273 shipyard buildings, 8 piers, 6 drydocks, and 659 homes in the surrounding area.

That’s Schuyler as in General Philip Schuyler, father of the Angelica, Elizabeth, and Peggy Schuyler and so Alexander Hamilton’s father-in-law. It’s a tenuous Hamilton connection, but I’ll take it.

That’s Schuyler as in General Philip Schuyler, father of the Angelica, Elizabeth, and Peggy Schuyler and so Alexander Hamilton’s father-in-law. It’s a tenuous Hamilton connection, but I’ll take it.

Finally, I discovered a door with a small brass plate. This may be the most stealthy museum I’ve yet visited. I tried the door, and it opened. So in I went.

Finally, I discovered a door with a small brass plate. This may be the most stealthy museum I’ve yet visited. I tried the door, and it opened. So in I went.

In 1915, Theda Bara, about 30, so-so looks, minor acting credits, exploded into the Madonna of her time. She ranks as the first ever “vamp” in cinema, playing a succession of seductresses and destroyers of men. Every femme fatale since traces her lineage back to Ms. Bara, Bayside resident.

In 1915, Theda Bara, about 30, so-so looks, minor acting credits, exploded into the Madonna of her time. She ranks as the first ever “vamp” in cinema, playing a succession of seductresses and destroyers of men. Every femme fatale since traces her lineage back to Ms. Bara, Bayside resident. But just in case anyone is curious about Bayside’s past, it does have a Historical Society, which occupies a little castle of a building on the grounds of nearby

But just in case anyone is curious about Bayside’s past, it does have a Historical Society, which occupies a little castle of a building on the grounds of nearby

Like many instutions of higher learning around the City, Hostos Community College has a small art space where they periodically mount public exhibitions.

Like many instutions of higher learning around the City, Hostos Community College has a small art space where they periodically mount public exhibitions.

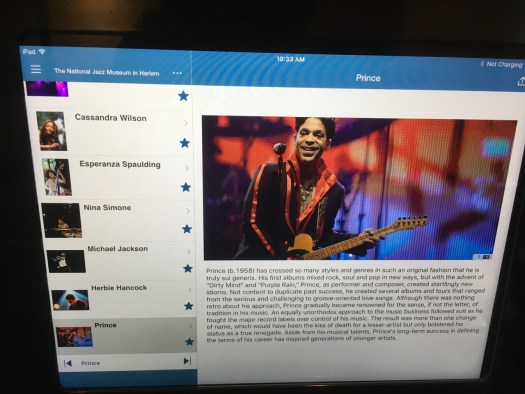

Visiting the National Jazz Museum made me think about the regular reports of the death of jazz, which may even be deader than opera at this point. I wondered if having a museum to it serves as yet another piece of evidence for the demise of the form? They have a display with photos of young jazz musicians, and sorta reach toward hip-hop, kinda. But really nothing I saw there suggests anything innovative or interesting has happened in jazz since the 1970s.

Visiting the National Jazz Museum made me think about the regular reports of the death of jazz, which may even be deader than opera at this point. I wondered if having a museum to it serves as yet another piece of evidence for the demise of the form? They have a display with photos of young jazz musicians, and sorta reach toward hip-hop, kinda. But really nothing I saw there suggests anything innovative or interesting has happened in jazz since the 1970s.

The China Institute occupies second floor space in a fairly anonymous office building in the Financial District. It appears they will soon move to much more prominent ground-floor space, which should help drive awareness and attract visitors.

The China Institute occupies second floor space in a fairly anonymous office building in the Financial District. It appears they will soon move to much more prominent ground-floor space, which should help drive awareness and attract visitors.