| Edification value | |

|---|---|

| Entertainment value | |

| Should you go? | |

| Time spent | 39 minutes |

| Best thing I saw or learned | The Visitor Center focuses quite a bit on the efforts at balancing the human desire to learn from the skeletons and artifacts in the burial ground, with the human desire to treat those remains respectfully and not have them end up on dusty museum shelves for eternity. That’s a hard balance, and it’s valuable to have a glimpse into the conversations that led to the compromises they made. |

The African Burial Ground is a small monument overshadowed by the government buildings around Foley Square. As they were digging for a new federal building in 1991 they discovered bodies, and from there re-discovered a forgotten cemetery used by the city’s African American population in the late 1600s and early 1700s.

The African Burial Ground is a small monument overshadowed by the government buildings around Foley Square. As they were digging for a new federal building in 1991 they discovered bodies, and from there re-discovered a forgotten cemetery used by the city’s African American population in the late 1600s and early 1700s.

Today a corner of what used to be the cemetery is a small green open space with a black granite monument, standing in for a headstone. There aren’t any markers, of course, and if it weren’t for the signs and a series of low humps of earth, you’d probably just think it was a pocket park. It’s not the whole extent of the cemetery, as this city is sufficiently about commerce and building that it won’t let the past fully forestall progress, even when that past includes the earthly remains of slaves.

Today a corner of what used to be the cemetery is a small green open space with a black granite monument, standing in for a headstone. There aren’t any markers, of course, and if it weren’t for the signs and a series of low humps of earth, you’d probably just think it was a pocket park. It’s not the whole extent of the cemetery, as this city is sufficiently about commerce and building that it won’t let the past fully forestall progress, even when that past includes the earthly remains of slaves.

You can visit the national monument in just a few minutes. However, the as is the norm with the National Park Service, the visitor center’s exhibits are simple, thoughtful, and earnest, and merit spending some time and contemplation.

It looks at what we know about the people laid to rest at the Burial Ground — nothing in terms of written records, but quite a bit based on archaeological evidence. It also talks a bit about contemporary black residents of New York about whom we do know something, and paints an unflinching picture of the hardships they faced.

The narrative of the visitor center speaks of “ancestors” (the remains of the people they dug up) and “descendants” (the modern activists who argued for humane treatment of those remains. It forges a compelling but unproveable link– we don’t know the names of those who were buried there, and there probably isn’t enough DNA in bones that old to connect them with certainty to any living person. Without a doubt, though, they were New Yorkers, and it seems very right that there is a space in the heart of the civic center of the city to note and remember the role that they played.

The African Burial Ground is definitely not entertaining. But it is important. Every New Yorker and everyone with an interest in the city and its history should go and pay their respects.

The African Burial Ground is definitely not entertaining. But it is important. Every New Yorker and everyone with an interest in the city and its history should go and pay their respects.

For Reference:

| Address | 290 Broadway (Visitor Center) and corner of Duane and Elk Streets (National Monument), Manhattan |

|---|---|

| Website | nps.gov/afbg |

| Cost | Free |

I wasn’t sure what to expect from the Museum of Chinese in America (MOCA for short). I knew the space would be great — it was designed by Maya Lin. But having recently been a bit disappointed by

I wasn’t sure what to expect from the Museum of Chinese in America (MOCA for short). I knew the space would be great — it was designed by Maya Lin. But having recently been a bit disappointed by  MOCA is indeed a beautifully designed museum. The space is consists of a series of rooms that surround a central open atrium, which extends from a skylight down to the classrooms, office, and restrooms on the basement level. Scarred bare brick underscores the age of the building, and its more industrial heritage. And windows carved into the rooms around the atrium ensure there’s always some natural light filtering in. The windows aren’t just openings, though: videos projected onto them make them serve a very clever dual purpose — the videos are also visible, of course, from the atrium side of the glass as well.

MOCA is indeed a beautifully designed museum. The space is consists of a series of rooms that surround a central open atrium, which extends from a skylight down to the classrooms, office, and restrooms on the basement level. Scarred bare brick underscores the age of the building, and its more industrial heritage. And windows carved into the rooms around the atrium ensure there’s always some natural light filtering in. The windows aren’t just openings, though: videos projected onto them make them serve a very clever dual purpose — the videos are also visible, of course, from the atrium side of the glass as well. The educational program succeeds as well as the building does. MOCA does exactly what you’d expect: tells the story of the Chinese immigrant experience in the United States. The show is largely chronological, starting with Chinese immigration to build the railroads and the subsequent racist reactions to Chinese immigration in the 19th century, which led to laws that essentially prevented most Chinese immigration, as well as constraining the kinds of work Chinese immigrants could do.

The educational program succeeds as well as the building does. MOCA does exactly what you’d expect: tells the story of the Chinese immigrant experience in the United States. The show is largely chronological, starting with Chinese immigration to build the railroads and the subsequent racist reactions to Chinese immigration in the 19th century, which led to laws that essentially prevented most Chinese immigration, as well as constraining the kinds of work Chinese immigrants could do.

In addition to the main space, there are two areas for temporary exhibitions. They currently feature an awesome look at Chinese food in the US, featuring about 33 chefs. Wall projections show video interviews where they speak about their lives and work and their take on “authenticity.” The museum set up one room like a banquet, with place settings for each chef that includes a short bio. This is a missed opportunity in our photogenic food-obsessed instagram age: there should be pictures of each chef’s signature dish at their setting. Still it’s a fun show, including a collection of personally meaningful objects: cleavers, cutting boards, menus, and such. Martin Yan’s wok is there, and Danny Bowien’s favorite spoon.

In addition to the main space, there are two areas for temporary exhibitions. They currently feature an awesome look at Chinese food in the US, featuring about 33 chefs. Wall projections show video interviews where they speak about their lives and work and their take on “authenticity.” The museum set up one room like a banquet, with place settings for each chef that includes a short bio. This is a missed opportunity in our photogenic food-obsessed instagram age: there should be pictures of each chef’s signature dish at their setting. Still it’s a fun show, including a collection of personally meaningful objects: cleavers, cutting boards, menus, and such. Martin Yan’s wok is there, and Danny Bowien’s favorite spoon.

El Museo del Barrio is currently the northernmost of the “Museum Mile” museums, occupying a stately building on Fifth Avenue, just across 104th Street from the Museum of the City of New York. According to its website, it started in the early 1970s as a cultural center focused on Puerto Rico. It has since expanded its focus to cover all Latin American and Caribbean art and artists. After bouncing around East Harlem a bit it found its current home in the Heckscher Building in 1977.

El Museo del Barrio is currently the northernmost of the “Museum Mile” museums, occupying a stately building on Fifth Avenue, just across 104th Street from the Museum of the City of New York. According to its website, it started in the early 1970s as a cultural center focused on Puerto Rico. It has since expanded its focus to cover all Latin American and Caribbean art and artists. After bouncing around East Harlem a bit it found its current home in the Heckscher Building in 1977. The main show when I visited was of video art by Beatriz Santiago Muñoz, as well as selections she chose from the museum’s permanent collection. I run hot and cold with video art. On the one hand, two of the best, most memorable works of art I’ve seen in the past two years were video pieces. On the other hand, I am bored to tears with the vast majority of it. Muñoz’s work, largely non-narrative, did little for me. I lacked the eye or knowledge to understand how her selections from the permanent collection clicked with what she’s trying to do.

The main show when I visited was of video art by Beatriz Santiago Muñoz, as well as selections she chose from the museum’s permanent collection. I run hot and cold with video art. On the one hand, two of the best, most memorable works of art I’ve seen in the past two years were video pieces. On the other hand, I am bored to tears with the vast majority of it. Muñoz’s work, largely non-narrative, did little for me. I lacked the eye or knowledge to understand how her selections from the permanent collection clicked with what she’s trying to do. The other show featured recent acquisitions, definitely a common and valid theme for a museum, although given the small space available, I didn’t find it very edifying as far as key current trends in Latin or Caribbean art. I liked some of the pieces, but I also thought much of the work on view wasn’t especially “Latin.”

The other show featured recent acquisitions, definitely a common and valid theme for a museum, although given the small space available, I didn’t find it very edifying as far as key current trends in Latin or Caribbean art. I liked some of the pieces, but I also thought much of the work on view wasn’t especially “Latin.”

Without a doubt the Onassis Center was good for my vocabulary (which is very good to begin with). I picked up six new-to-me words, at least five of which I am sure I will find opportunities to use in the near future.

Without a doubt the Onassis Center was good for my vocabulary (which is very good to begin with). I picked up six new-to-me words, at least five of which I am sure I will find opportunities to use in the near future.

Halls of fame today are two-a-penny. Everyone and everything from minor league lacrosse to rock n roll has a hall of fame. But it wasn’t always that way. There had to be, at some point, a first one.

Halls of fame today are two-a-penny. Everyone and everything from minor league lacrosse to rock n roll has a hall of fame. But it wasn’t always that way. There had to be, at some point, a first one.

The Czech Center’s museum space is small but effective, and it comes associated with three things that no cultural institution I’ve seen thus far can match:

The Czech Center’s museum space is small but effective, and it comes associated with three things that no cultural institution I’ve seen thus far can match:

The Leslie-Lohman Museum occupies the newest museum space in the city, having moved into spiffy new digs in SoHo in just the last two weeks.

The Leslie-Lohman Museum occupies the newest museum space in the city, having moved into spiffy new digs in SoHo in just the last two weeks.  The new space for the museum is mostly terrific. You enter into a fairly narrow area where two greeters welcome you and point out what’s on. There are two gallery spaces, a smaller one to the left as you walk in , and a larger one to the right and back. There’s also a kitchen space as well. I am torn between thinking it’s charming that there’s a kitchen right sort of in the open, and thinking their architect really should’ve found a way to separate that from the public space.

The new space for the museum is mostly terrific. You enter into a fairly narrow area where two greeters welcome you and point out what’s on. There are two gallery spaces, a smaller one to the left as you walk in , and a larger one to the right and back. There’s also a kitchen space as well. I am torn between thinking it’s charming that there’s a kitchen right sort of in the open, and thinking their architect really should’ve found a way to separate that from the public space. The inaugural show is sort of a hodge-podge. I get that survey shows do that, and I would be disappointed if they’d segregated the gay art over here, the lesbian art over there, etc. Sorting by chronology or medium can oversimplify, too. But I would’ve appreciated some effort to put a lens on the collection. Love versus sex. Ideals of beauty. Something.

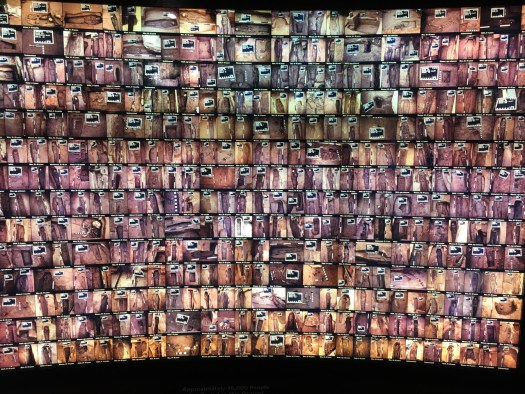

The inaugural show is sort of a hodge-podge. I get that survey shows do that, and I would be disappointed if they’d segregated the gay art over here, the lesbian art over there, etc. Sorting by chronology or medium can oversimplify, too. But I would’ve appreciated some effort to put a lens on the collection. Love versus sex. Ideals of beauty. Something. Should you go? It depends on how you feel about diversity and penises. And maybe, even if you are squeamish about either of those two things, you should consider going anyway. It might be good for you.

Should you go? It depends on how you feel about diversity and penises. And maybe, even if you are squeamish about either of those two things, you should consider going anyway. It might be good for you.

The Schomburg Center is the New York Public Library’s research branch focused on the African American experience. It’s a complex of three buildings in Harlem, hosting a ton of talks, events, and exhibitions. Much of the Schomburg Center is currently undergoing a thorough renovation, so I couldn’t visit anything beyond the exhibition space.

The Schomburg Center is the New York Public Library’s research branch focused on the African American experience. It’s a complex of three buildings in Harlem, hosting a ton of talks, events, and exhibitions. Much of the Schomburg Center is currently undergoing a thorough renovation, so I couldn’t visit anything beyond the exhibition space. The current show at the Schomburg Center is on the Black Power movement of the late 60s and 70s. (2016 marked its fiftieth anniversary) Well chosen quotes highlighted the establishment reaction to the Black Power movement, actual newspapers, magazines, flyers, photographs, pins and other key documents made an exhibit that involved a great deal of reading much more immediate and interesting. Music from the era helped convey the emotion of the time. And some well chosen videos on a couple of screens added variety.

The current show at the Schomburg Center is on the Black Power movement of the late 60s and 70s. (2016 marked its fiftieth anniversary) Well chosen quotes highlighted the establishment reaction to the Black Power movement, actual newspapers, magazines, flyers, photographs, pins and other key documents made an exhibit that involved a great deal of reading much more immediate and interesting. Music from the era helped convey the emotion of the time. And some well chosen videos on a couple of screens added variety. The show covers a large amount of ground, reflecting on the political and

The show covers a large amount of ground, reflecting on the political and  organizational tactics of the Black Power leadership, as well as on the movement’s impact on fashion, the arts, and popular culture. I confess I always wondered about the berets that were such a signature part of the Black Power look. The show suggests they came from the influence of Che Guevara and Fidel Castro.

organizational tactics of the Black Power leadership, as well as on the movement’s impact on fashion, the arts, and popular culture. I confess I always wondered about the berets that were such a signature part of the Black Power look. The show suggests they came from the influence of Che Guevara and Fidel Castro. The Schomburg’s exhibition space itself is beautiful, light and airy, with big windows. It’s not large, but it was the right size for the show it contained.

The Schomburg’s exhibition space itself is beautiful, light and airy, with big windows. It’s not large, but it was the right size for the show it contained.  And for reasons that I have yet to quite figure out, a brownstone tucked away on a side street in Morningside Heights is home to a museum of his art, along with works he collected in his journeys.

And for reasons that I have yet to quite figure out, a brownstone tucked away on a side street in Morningside Heights is home to a museum of his art, along with works he collected in his journeys. Roerich’s early paintings led to him working on stage design for operas and ballets for the many of the great late 19th/early 20th century Russian composers, including Stravinsky as mentioned above. His stage work extended to Wagner and designs for plays by playwrights outside Russia as well. Even his later paintings often have a sort of backdroppy, set designish look to me. His landscapes are very still and serene, often distant mountains. It’s easy to imagine great events unfolding in some unpainted foreground.

Roerich’s early paintings led to him working on stage design for operas and ballets for the many of the great late 19th/early 20th century Russian composers, including Stravinsky as mentioned above. His stage work extended to Wagner and designs for plays by playwrights outside Russia as well. Even his later paintings often have a sort of backdroppy, set designish look to me. His landscapes are very still and serene, often distant mountains. It’s easy to imagine great events unfolding in some unpainted foreground.

The Roerichs moved around a lot during the tumultuous 20th century. They got into yoga and developed their own brand of theosophy, creating a group called the Agni Yoga Society, which was (quoting from the museum brochure) “dedicated to the recording and dissemination of a living ethic that would encompass and synthesize the philosophies and religious teachings of all ages.” Small dreams…

The Roerichs moved around a lot during the tumultuous 20th century. They got into yoga and developed their own brand of theosophy, creating a group called the Agni Yoga Society, which was (quoting from the museum brochure) “dedicated to the recording and dissemination of a living ethic that would encompass and synthesize the philosophies and religious teachings of all ages.” Small dreams… I’m amazed it’s taken me this long to go to the Nicholas Roerich Museum. I live literally three blocks from it, I have no excuses. Is it mind boggling? Does everyone have to go? No, and no. But it’s a perfect example of how this city hides treasures behind anonymous rowhouse facades on anonymous streets in random neighborhoods. If you’re nearby and feeling stressed, take 30 minutes and drop in. I wager you will leave feeling better for it.

I’m amazed it’s taken me this long to go to the Nicholas Roerich Museum. I live literally three blocks from it, I have no excuses. Is it mind boggling? Does everyone have to go? No, and no. But it’s a perfect example of how this city hides treasures behind anonymous rowhouse facades on anonymous streets in random neighborhoods. If you’re nearby and feeling stressed, take 30 minutes and drop in. I wager you will leave feeling better for it.