| Edification value | |

|---|---|

| Entertainment value | |

| Should you go? | |

| Time spent | 73 minutes |

| Best thing I saw or learned |  A pair of Christian Louboutin boots laboriously decorated with antique glass beads by Jamie Okuma, of the Louiseño and Shoshone-Bannock tribes. A pair of Christian Louboutin boots laboriously decorated with antique glass beads by Jamie Okuma, of the Louiseño and Shoshone-Bannock tribes. |

The National Museum of the American Indian’s George Gustav Heye Center is one of the Smithsonian Institution’s two New York outposts (along with the Cooper-Hewitt). It could be the museum with the longest name in the city.

The National Museum of the American Indian’s George Gustav Heye Center is one of the Smithsonian Institution’s two New York outposts (along with the Cooper-Hewitt). It could be the museum with the longest name in the city.

You may think, “But doesn’t the Smithsonian have a National Museum of the American Indian on the Mall in D.C.?” Yes, it does. The Heye Center in New York came first, though. It started as the Museum of the American Indian, opening in Harlem way back in 1922, to display George Gustav Heye’s expansive collection of Native American arts and crafts. In due course, the Smithsonian took over. While it started planning for the D.C. museum (which opened in 2004) in the 1990s, it also opted to keep a New York outpost.

The Building

Today, the National Museum of the American Indian makes its home in a spectacular Beaux Arts building at the southern end of Broadway. The architect Cass Gilbert designed the Alexander Hamilton U.S. Customs House, which opened in 1907. (The name is the sole Hamilton connection, but I’m counting it!) A monument to commerce wrought in stone, it’s a far grander and more prominent building than Federal Hall National Memorial, which also was built as a customs house.

Truly it’s a magnificent piece of architecture, festooned with allegorical sculptures and heroic traders and all manner of artsy ornamentation. Daniel Chester French, the sculptor of Lincoln at the Lincoln Memorial, did four figures representing the major regions of the world. Pictured here, fittingly, is “America.”

Inside some bits of historic grandeur remain, too. A matched set of swirly spiral staircases graces the corners. And the building centers on a –I know I already used the word “spectacular” but I’m using it again deliberately–spectacular oval rotunda. I wish they did more with that space! It features some benches, ratty carpeting, and brass light fixtures currently. But really it cries out to be a fancy cafe or something. I suspect the building’s landmark status prevents altering the rotunda to make better use of its potential. Too bad. The rotunda perimeter features Reginald Marsh murals of New York City, ships in the harbor, and historic figures important in trade in the United States– people like Columbus and Henry Hudson, whose presence seems more than a little ironic in the context of the building’s current use.

Indeed, the idea of turning a building focused on trade, from an era that unabashedly glorified the commercial impulses that ended up dispossessing the Native American tribes of their lands, into a museum for those nations…well. I find it pretty ironic.

Indeed, the idea of turning a building focused on trade, from an era that unabashedly glorified the commercial impulses that ended up dispossessing the Native American tribes of their lands, into a museum for those nations…well. I find it pretty ironic.

Or perhaps fair and fitting: why not have a colonization work in the other direction for once?

The Exhibits

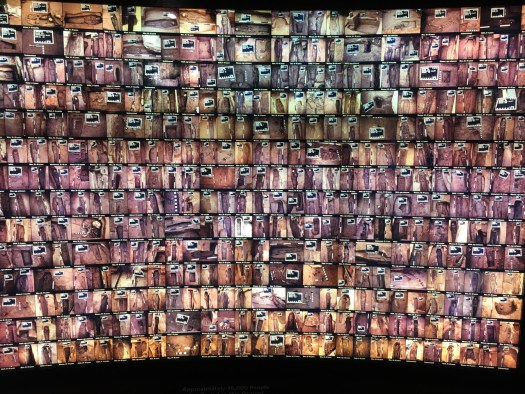

The Heye Center divides into three galleries. One of them hosts a permanent exhibit on the Native American nations. The other two feature changing exhibits. When I visited, one focused on Central American pottery, and the other looked at contemporary Native American fashion designers.

I’m particularly impressed that the Heye Center would put on something like the fashion show. My stereotypical view of a Native American Museum would be all tradition and dusty artifacts. I like that they care to show how American Indians today carry their traditions forward, creating both beautiful things and successful businesses. It seems a through-line of the place that the objects on display represent more than just, well, museum pieces.

The permanent exhibit, titled “Infinity of Nations,” is somewhat dense and dusty, and tries valiantly to do justice to an entire continent’s worth of tribes and traditions in a fairly small space. That said, as a native of Hawai’i, I felt slightly vexed that the museum sticks just to the continent.

However, I did very much like how the permanent collection intersperses descriptive wall texts with occasional signed ones, written by tribal representatives and other experts on Indian cultures. The specific voices create an immediacy that most museum texts lack, reminding visitors that these cultures still value these objects and their creators. For the same reason, I like how the collection includes contemporary arts and crafts. Finally, I also appreciate the way the curators deployed just a few touchscreens to offer deeper dives into key objects. It felt like they chose the right things.

On balance, the Heye Center seems to maintain a good relationship with Native American communities. Of course, I’ve only got their word on that. But (a) Heye paid for all the items in his collection, didn’t just loot them, (b) many seem to realize that had he not treasured and saved these things, they likely would no longer exist, and (c) the Museum allows the tribes liberal access to the collections, for both study and ceremonial purposes.

The Bottom Line

Everyone should visit the Heye Center. More than I expected, it depicts American Indian cultures as vital, living things. And it does so in creative ways, via (at least sometimes) inventive, unexpected exhibits. Even if you’ve been to the D.C. National Museum of the American Indian, coming here might still offer new things to look at and to think about. And the building is, as I may have mentioned, spectacular.

For Reference:

| Address | One Bowling Green, Manhattan |

|---|---|

| Website | si.edu |

| Cost | Free |

| Other Relevant Links |

|

The current church is Gothic Revival, in brownstone, which always seems to me a striking and unlikely choice. Until this visit I never wondered what the surrounding area was like when it was built — if it was all brownstone rowhouses, it would’ve fit in nicely I suppose. Now it stands out, even as the surrounding skyscrapers far overtop it.

The current church is Gothic Revival, in brownstone, which always seems to me a striking and unlikely choice. Until this visit I never wondered what the surrounding area was like when it was built — if it was all brownstone rowhouses, it would’ve fit in nicely I suppose. Now it stands out, even as the surrounding skyscrapers far overtop it. Trinity’s history goes back to 1697, but this is the third church on this site. The first Trinity Church burned down in the Great Fire during the revolution in 1776. The second revealed structural problems following a severe snowstorm in 1838 that led to its replacement with the current building in 1846. So while it’s old, it’s not as old as it might want you to believe. St. Paul’s Chapel, a Trinity offshoot a short stroll north on Broadway, dates to 1766. I strongly recommend visiting both if you have time.

Trinity’s history goes back to 1697, but this is the third church on this site. The first Trinity Church burned down in the Great Fire during the revolution in 1776. The second revealed structural problems following a severe snowstorm in 1838 that led to its replacement with the current building in 1846. So while it’s old, it’s not as old as it might want you to believe. St. Paul’s Chapel, a Trinity offshoot a short stroll north on Broadway, dates to 1766. I strongly recommend visiting both if you have time. The interior of Trinity is pretty, but not especially noteworthy. It’s on a par with most other gothic revival churches in the U.S. or U.K.

The interior of Trinity is pretty, but not especially noteworthy. It’s on a par with most other gothic revival churches in the U.S. or U.K. Anyone who likes old churches or cemeteries or Hamilton (or Robert Fulton) must visit Trinity. Moreover, the graveyard is an oasis of green in a part of the city that doesn’t have a lot of that. For those frantically visiting all of Lower Manhattan’s many historic sites, museums, and other landmarks, it represents a chance to catch one’s breath in the midst of a jam-packed day. Trinity also has a fine music program–definitely take a look at their website. Even for a casual visitor, Trinity is worth a special trip.

Anyone who likes old churches or cemeteries or Hamilton (or Robert Fulton) must visit Trinity. Moreover, the graveyard is an oasis of green in a part of the city that doesn’t have a lot of that. For those frantically visiting all of Lower Manhattan’s many historic sites, museums, and other landmarks, it represents a chance to catch one’s breath in the midst of a jam-packed day. Trinity also has a fine music program–definitely take a look at their website. Even for a casual visitor, Trinity is worth a special trip.

Federal Hall is not what it seems. In fact, it’s not Federal Hall at all. From the outside a passer-by might easily believe that it was the first capitol of the U.S., and the building where George Washington took the oath as president. I thought that for years; only recently did I realize: right location, wrong building.

Federal Hall is not what it seems. In fact, it’s not Federal Hall at all. From the outside a passer-by might easily believe that it was the first capitol of the U.S., and the building where George Washington took the oath as president. I thought that for years; only recently did I realize: right location, wrong building.

But I couldn’t help get the sense that the National Park Service would trade today’s building if they could get the “real” Federal Hall back again.

But I couldn’t help get the sense that the National Park Service would trade today’s building if they could get the “real” Federal Hall back again.

The South Street Seaport Museum just celebrated its 50th anniversary, and its establishment contributed to the survival of a collection of historic buildings in the face of Lower Manhattan’s relentless pressure for development. The museum includes a print shop (worth visiting; great cards), the museum building proper, and the “street of ships,” a collection of historic vessels, several of which are open for tours when the museum is open.

The South Street Seaport Museum just celebrated its 50th anniversary, and its establishment contributed to the survival of a collection of historic buildings in the face of Lower Manhattan’s relentless pressure for development. The museum includes a print shop (worth visiting; great cards), the museum building proper, and the “street of ships,” a collection of historic vessels, several of which are open for tours when the museum is open.

The African Burial Ground is a small monument overshadowed by the government buildings around Foley Square. As they were digging for a new federal building in 1991 they discovered bodies, and from there re-discovered a forgotten cemetery used by the city’s African American population in the late 1600s and early 1700s.

The African Burial Ground is a small monument overshadowed by the government buildings around Foley Square. As they were digging for a new federal building in 1991 they discovered bodies, and from there re-discovered a forgotten cemetery used by the city’s African American population in the late 1600s and early 1700s. Today a corner of what used to be the cemetery is a small green open space with a black granite monument, standing in for a headstone. There aren’t any markers, of course, and if it weren’t for the signs and a series of low humps of earth, you’d probably just think it was a pocket park. It’s not the whole extent of the cemetery, as this city is sufficiently about commerce and building that it won’t let the past fully forestall progress, even when that past includes the earthly remains of slaves.

Today a corner of what used to be the cemetery is a small green open space with a black granite monument, standing in for a headstone. There aren’t any markers, of course, and if it weren’t for the signs and a series of low humps of earth, you’d probably just think it was a pocket park. It’s not the whole extent of the cemetery, as this city is sufficiently about commerce and building that it won’t let the past fully forestall progress, even when that past includes the earthly remains of slaves.

The African Burial Ground is definitely not entertaining. But it is important. Every New Yorker and everyone with an interest in the city and its history should go and pay their respects.

The African Burial Ground is definitely not entertaining. But it is important. Every New Yorker and everyone with an interest in the city and its history should go and pay their respects.